By Jill Sirko, PhD

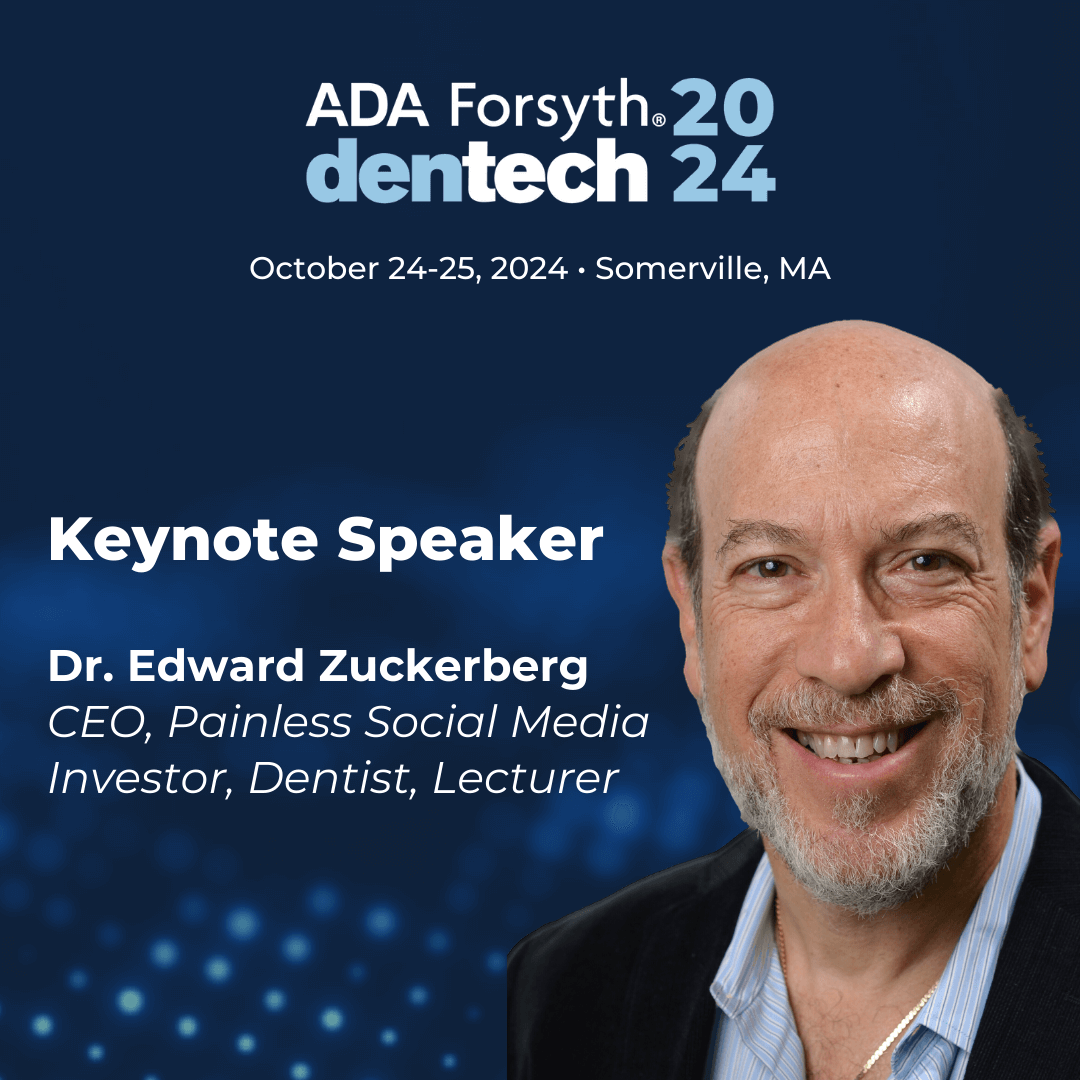

Dr. Edward Zuckerberg, father to Meta CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, will be delivering the keynote address at dentech 2024. Ahead of the conference, he discussed his journey into dentistry, his early adoption of technology including digital radiography, and online banking, which significantly improved patient case acceptance and practice efficiency. Dr. Zuckerberg also shared his transition to consulting and venture capital, focusing on companies like VIOME and Keystone Bio, which address oral health’s systemic impact. He envisions a future where dentists are integrated into primary care, leveraging technologies to enhance patient outcomes and reduce healthcare costs.

Q: How did you get into dentistry?

Dr. Zuckerberg: I grew up in New York City in the 50s, and financial independence was important to my parents. They wanted us to become professionals—doctors, lawyers, or accountants. I applied to various professional schools and got into dental school. I remember my first day of dental school hearing some of the upperclassmen talking about a bridge, and I didn’t know if they were talking about the Brooklyn Bridge or the Verrazano Bridge. I clearly didn’t know anything about dentistry.

We didn’t have regular dental care, and I had no family background in dentistry, unlike many of my peers at New York University College of Dentistry. But I loved working with my hands and people, and it turned into a great career for me.

Q: But no pressure on your children to become dentists as well?

Dr. Zuckerberg: Our dental office was in my house. All our children were exposed to the dental office on a regular basis. But it was important to us that they were free to choose their own paths. My wife had a lot of pressure to become a physician, and it was a very poor choice for her. She was a psychiatrist, but she eventually left that work and became my office manager. She was the most overqualified dental office manager in the world.

We made a very conscious decision to foster our children’s passions and enrich their lives with things that they enjoyed, and were good at. We wanted to help them find careers that suited them. So, I think we’ve been blessed, and I think that’s turned out really well for all four of our kids.

Q: How did your journey into technology begin, especially in relation to your dental practice?

Dr. Zuckerberg: Well, I’ve always had a bit of a techie side, even before it was common in dental practices. Back in 1981, shortly after my wife and I moved to Westchester County, I found myself testing Citibank’s new online banking system using an Atari 800. At the time, the idea of doing banking from a computer was revolutionary! It took me about an hour to pay three bills, but I remember thinking, this is going to change everything.

That fascination with technology started to creep into my dental practice soon after. In 1985 when I bought the IBM PC XT, which was one of the first personal computers available, I paired it with some very basic dental management software. The whole setup cost $10,000, and although it couldn’t even store a single image from today’s digital cameras, it ran my office systems. It felt groundbreaking at the time. A few years later, in 1988, I digitized my appointment book, moving away from the traditional handwritten schedules. That was a big deal back then!

Q: How did you use technology to improve patient care?

Dr. Zuckerberg: One of the biggest challenges is getting patients to understand their treatment plans. In the late 1980s, I used one of the first intraoral cameras, which helped patients visualize their issues. It eased dental phobia and increased case acceptance. I also adopted digital radiography in 1998, allowing patients to see high-quality X-rays on a 21-inch screen. It made a big difference.

Q: How did you become more involved in lecturing to the broader dental community?

Dr. Zuckerberg: In 2010, I got a call from Dr. Howard Farran, the founder of Dentaltown, a leading online dental community. He had a problem with his Facebook page and, knowing that I was a dentist, reached out to me for help. Howard wanted to become friends on Facebook with every dentist in the world, but he had reached the 5,000-friend limit and wanted help turning his profile into a business page. I guided him through the process, which led to writing my first article on social media for dentists, called “Does My Office Really Need a Facebook Page?”

It was well-received and marked the beginning of a new chapter in my career. Soon after, I was invited to write more articles. I started lecturing at dental societies and study groups at dental schools. I also started advising dental startups on product development and helping colleagues understand how to incorporate new technology into their practices.

Q: Looking back, what’s been the most rewarding part of embracing technology in dentistry?

Dr. Zuckerberg: For me, it’s always been about improving patient care while making the practice more efficient. Seeing patients understand their treatment and agree to necessary care because of the technology we use—that’s incredibly rewarding. Plus, helping the next generation of dentists see the value in these innovations has been a great honor. I never set out to become a tech expert, but technology has absolutely transformed my career and the way I approach dentistry.

Q: And now you are a venture partner at Revere Partners? Can you tell us more about that?

Dr. Zuckerberg: Jeremy Krell and I had crossed paths at several dental conferences, as we both advised numerous dental startups. In 2021, Jeremy called me up to tell me he had started a venture capital firm called Revere Partners, focusing on dental startups. He asked if I wanted to join and help shape the future of these startups, particularly those leveraging technology and innovation.

At Revere, I was doing much of what I had been—working with high-tech companies in AI, like Pearl and Overjet, companies with smart toothbrushes, Perceptive, a robotics company that drills crown preparations with a robot. But then something different came along. In March 2021, I took a call with a team from Keystone Bio, a company that was working on something completely outside of my usual scope: a monoclonal antibody that could eradicate P. gingivalis, a bacteria linked to gum disease.

At first, I wasn’t sure what to make of it. My knowledge of P. gingivalis was minimal. But during that one-hour call, I was blown away by what they were talking about. This wasn’t just about dental care—this was about preventing major systemic diseases like Alzheimer’s, heart disease, and diabetes. Halfway through the call, I grabbed my wife, who has a medical background, and said, “You have to hear this.”

Q: What was it about Keystone Bio that made you so excited?

Dr. Zuckerberg: We’ve known for a while that oral disease has systemic effects, but the connection was always vague. We’d tell patients that gum disease could lead to issues in other parts of the body, but we didn’t fully understand how. Keystone Bio’s research was groundbreaking. They weren’t just managing gum disease—they were looking at preventing bacteria like P. gingivalis from entering the bloodstream, where it can cause serious diseases.

I’ve seen the tragic outcomes of untreated gum disease. I once had a 42-year-old patient with severe periodontal disease who refused treatment. Four years later, he died from a massive heart attack. Another patient, five months pregnant, came in with an abscessed tooth. I treated her, but she delayed further care—and tragically, she lost the baby in her seventh month. Were these health outcomes directly related to their oral health? Probably. These experiences stayed with me, and when Keystone Bio presented their research, it all started to connect. This was bigger than dentistry.

Q: You’ve also mentioned working with VIOME. How did that come about?

Dr. Zuckerberg: That was a serendipitous moment. I was listening to my daughter’s business radio show on SiriusXM, and she had a guest talking about P. gingivalis. I couldn’t believe it! My daughter isn’t a scientist—her background is in marketing and media. Anyway, the guest was Naveen Jain, CEO of VIOME. VIOME is a company focused on gut health and oral diagnostics and they have developed the first non-invasive oral cancer detection test based on a salivary sample. It has a 95% degree of sensitivity, which intrigued me since the five-year survival rate for this cancer remains at just 50%. I eventually joined VIOME as Chief Dental Officer, and we’re working on bringing this groundbreaking test to market.

Q: From your perspective, what trends do you think are most exciting to watch right now?

Dr. Zuckerberg: We can’t ignore AI, right? I’m advising companies that are using AI for interpreting digital X rays. I have a company now called Velmeni that is using AI to analyze cone beam, which I think is huge. Cone beam has a largely untapped benefit of determining airway space, and most dentists are not trained to interpret cone beams to determine the course of treatment recommended for patients with sleep apnea or varieties of airway impediments. Velmeni is pioneering in using AI to incorporate that data from cone beams to do that. That to me, that’s exciting. Another one of my companies, Yobi, is using AI to develop alternatives for patients calling dental offices. AI gets me excited. And of course, I am incredibly passionate about new technologies that use salivary diagnostics to provide insights on what’s going on in our health.

Where do you see dentistry in 10 years?

Dr. Zuckerberg: I think 10 years from now, dentistry will be integrated with medical facilities. The initial triage for a patient’s systemic disease complaint will include an oral exam. We’re not going to touch a patient with possible diabetes until we know this patient has no gum disease. Because we can’t begin to treat any of the other systemic illnesses without eliminating one of the known causes of pathology that lead to these systemic problems.

This interview was edited for clarity and length.