An estimated total of one trillion species of bacteria exist in the world, with only about 30,000 species discovered and named.

While scientists are aware of many unnamed, unstudied microorganisms, they remain understudied because these microbes haven’t been cultured in a laboratory. These illusive microorganisms are known by microbiologists as “microbial dark matter.”

Dr. Xuesong He of ADA Forsyth marked a breakthrough in 2015 when he cultured Saccharibacteria, or TM7. TM7, previously considered to be microbial dark matter, is part of a newly identified group of bacteria called Patescibacteria, also known as Candidate Phyla Radiation, which has been estimated to make up a quarter or even half of all bacterial diversity in the world.

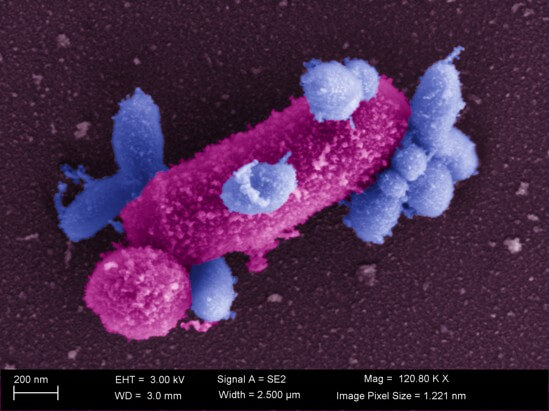

Most remarkably discovered by Dr. He, these bacteria grow on other host bacteria, creating an episymbiotic relationship, an aspect which was largely unknown and underexplored.

Through an R01 grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Dr. Batbileg Bor continues to explore TM7 with Dr. He, illuminating key information about how Saccharibacteria interacts with its host bacterium and human cells.

The most interesting part of this research to me is the unknown. We essentially have no idea the exact mechanisms by which TM7 interacts with the human host.

Batbileg Bor, PhD

Dr. Bor worked as a Postdoctoral Fellow with Dr. He under Dr. Wenyuan Shi before rising to Associate Member of Staff at the ADA Forsyth Institute. They collaborated in exploring many yet-unknown characteristics of Saccharibacteria.

“The most interesting part of this research to me is the unknown,” Dr. Bor said. “We essentially have no idea the exact mechanisms by which TM7 interacts with other microbes or the human host.”

TM7 was first discovered in a peat bog in Germany, and the name “TM” comes from the German term “Torf, Mittlere Schicht” which translates to “peat, middle layer.” This ultrasmall bacterium has also been discovered in rainforest soil, plant sludge, cockroaches, gold mines, and in the mouths of mammals such as cows, dogs, dolphins and humans.

In the human oral cavity, TM7 is an episymbiotic bacterium which attaches to Actinomyces, a potential pathobiont in periodontal disease. A pathobiont is a microorganism which is normally present in a microbial ecosystem but could become pathogenic under certain conditions.

Actinomyces does not cause periodontitis, but it gathers at the site of the disease and may push the disease to a more severe state.

TM7’s episymbiotic relationship with Actinomyces and their increased relative abundance in disease initially suggested that the bacterium contributes to disease.

“Everybody automatically thought that TM7 was bad – these bacteria might be initiating or causing a disease,” Dr. Bor said.

However, scientists in the Bor Lab uncovered that TM7 might in fact mitigate disease. In a mouse model, inflammation and subsequent bone loss was alleviated when TM7 was added to the host bacteria, compared to its progression with the host bacteria alone.

The possibility that TM7 can reduce inflammation or protect against disease delivers exciting potential use as a therapeutic mechanism.

Much remains unknown about TM7. Researchers are still determining why some TM7s bind with certain sets of Actinomyces species, but not others. Importantly, there is also much left to discover about the way TM7 interacts with human cells.

“How are TM7 decreasing inflammation, exactly?” Dr. Bor said. “The question is, if TM7 is reducing inflammation when they are present, is it because they are somehow inhibiting this host bacteria and its pathogenicity, or is it actually working directly on human cells, interacting with the human host?”